Hans Ulrich Obrist im Gespräch mit der Choreografin Meg Stuart über Rituale, Improvisation und Ekstase. Gekürzte Fassung; der vollständige Artikel erschien im Magazin der Kulturstiftung des Bundes # 30 Frühjahr/Sommer 2018

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Ekstase, Transzendenz und Ausdauer sind spannende Themen, weil ich denke, dahinter steckt die Idee, dass Kunst eine Art Portal ist, durch das man hindurch muss. Aber erstmal möchte ich dich fragen, wie es bei dir alles anfing. Wie bist du zu Tanz und Choreografie gekommen, gab es da eine Art Erweckungserlebnis?

Meg Stuart: Ich bin im Theater aufgewachsen, das spielte sicherlich eine große Rolle. Meine Eltern sind beide Theaterregisseure. Viele Theaterstücke zu sehen, Tänzer und Schauspielerinnen genau beobachten zu können, das hat Eindruck hinterlassen. Aber irgendwie wollte ich nie mitspielen, keine Charaktere darstellen, sondern ich wollte ich selbst sein. Zunächst habe ich viel Sport gemacht, bin gelaufen, das Körperliche war wichtig, und so kam es, dass ich mich immer mehr dem Tanz angenähert habe, und irgendwann ließ ich das Laufen sein. Und dann bin ich in einen Tanzkurs in der High School gegangen, in dem es nicht darum ging, zu lernen, sich wie andere zu bewegen – obwohl ich auch das getan habe –, sondern eigentlich um Choreografie. Da habe ich choreografische Studien gemacht – stehend, sitzend, liegend –, habe die einzelnen Körperteile, den ganzen Körper rauf und runter untersucht. Und dann fing ich irgendwie an, mir Tänze auszudenken, bevor ich wirklich wusste, wie man tanzt. Ich hatte keine Technik, die ich später wieder hätte verlernen müssen, sondern musste vielmehr eine Struktur und Technik um mich herum erst aufbauen, um die Dinge umzusetzen, die ich mir vorgestellt hatte. Ich habe damals alternative Techniken ausprobiert, aber natürlich auch die „modernen Meister“ studiert: Cunningham, Graham, Limón. Ich weiß nicht, ob man das eine Offenbarung nennen kann, aber so habe ich angefangen.

HO: Du kommst ursprünglich aus New Orleans …

MS: Ja, ich stamme aus New Orleans, aber meinen Durchbruch als Künstlerin hatte ich beim Klapstuk Festival in Belgien mit „Disfigure Study“ (1991), da war ich 26 Jahre alt. Bis dahin hatte ich schon eine Reihe von kleineren Studien in New York gemacht, die dann in „Disfigure Study“ zusammenkamen. Mit diesem ersten abendfüllenden Stück hatte ich dann einen Fuß in der europäischen Szene.

HO: Deine eigene „Sprache“ hast du also erst in Belgien wirklich gefunden. Das erste Stück von dir, auf das ich aufmerksam wurde, war „No Longer Readymade“ (1993). Das traf auf große Resonanz in der Kunstwelt. Was hatte es mit „No Longer Readymade“ auf sich?

MS: Es war mein zweites Stück, und vielleicht entstand es aus einer Krise heraus. Ein zweites Werk machen, während ich auf Tournee mit dem ersten war, sehr schnell viel Aufmerksamkeit bekommen, aus New York wegziehen und in die europäische Festivalszene reinkommen – das war ganz schön viel auf einmal. Das Kernstück dieser Arbeit ist ein Solo. Ich grabe mich durch den Müll in meinen Taschen, Quittungen und Münzen und solche Sachen, ich schütte sozusagen die Überreste eines Lebens auf den Boden. […] diesmal war es eine ganz neue Beschäftigung mit der Frage: Here I am, what now? […] Es war das erste Mal, dass ich physische und emotionale Körperzustände erforschte. Das Stück beginnt damit, dass der Tänzer, Benoît Lachambre, seinen Kopf für etwa 4 1⁄2 Minuten heftig schüttelt und dann fieberhaft gestikuliert. Dann fängt er wieder an zu zittern und macht das Ganze rückwärts. Er ist völlig außer Kontrolle, er verschwimmt wie in einer Art Bruce-Nauman-Video, er geht an seine Grenzen, aber er artikuliert sich in diesem Wahnsinn. Als wir anfingen, diese Szene zu proben, übergab er sich im Studio. Erst nach vielen Proben war er schließlich imstande, sie durchzuführen. Es war das erste Mal, dass ich mich für Fieber oder Schweiß interessierte – könnte das eine „Sprache“ sein? Wie nutzen wir diese Art von unfreiwilligen Körperreaktionen als Tanzmaterial? So begann ich, mit physischen und emotionalen Zuständen choreografisch zu arbeiten.

HO: Dieses Stück scheint über das Rationale hinauszugehen, irrationale Kräfte kommen ins Spiel. Andrej Tarkowskij sagte einmal, dass wir Rituale wieder einführen müssen, weil sie in der modernen Welt verschwunden seien. Interessant ist, dass Ekstase in indigenen Kulturen und auch in einem rituellen Kontext als etwas sehr Positives angesehen wird. Aber im Kapitalismus und in unserer globalisierten Welt hat man irgendwann angefangen, sie negativ zu konnotieren. In deiner Arbeit hat sie eindeutig eine positive Konnotation. Ich habe mich gefragt, wann das in deine Arbeit eingeflossen ist. Als du damit anfingst, muss das ziemlich ungewöhnlich gewesen sein, oder?

MS: Ich denke, aus westlicher Perspektive sind Rituale Dinge, die wir aus Gewohnheit tun, wenn auch nicht aus freien Stücken, aber wir sind ständig mit Ritualen beschäftigt. Wir erschaffen sie für uns selbst – wir sind gezwungen, bei denen der anderen mitzumachen, wir sind ständig von Ritualen umgeben. Es geht also darum, sie anzuerkennen, aber auch, sie neu zu erfinden. Wir werden täglich von dem beeinflusst, was wir sehen, unser Bewusstsein wird mit Informationen überschwemmt. Die Frage ist, wie gehen wir damit um, wie machen wir uns davon frei, welche Gedanken gehören uns, welche nicht, und wie können wir mit diesen Kräften arbeiten? […]

HO: Sehr beeindruckend ist auch dein Stück „Until Our Hearts Stop“ (2015), das ich in London sah. Das hat auch mit diesem anderen Zustand zu tun. Denn dort benutzt du, wie auch in den früheren Stücken, oft den Begriff der Erschöpfung, und wie Erschöpfung zu einem transzendentalen Zustand führen kann …

Erschöpfung ist entweder ein Wunsch oder ein Problem, aber sie kann auch eine Strategie sein, um Kunst zu machen.

MS: … oder zu einem Nervenzusammenbruch (lacht). Aber ich glaube, dass wir auch gerne erschöpft sind, ich glaube, dass Erschöpfung ein Zustand des Im-Moment-Seins ist, es ist unser neoliberaler Modus, diese Idee des Immer-Arbeitens. Es geht auch darum, durch die Erschöpfung hindurchzugehen, um einen höheren Bewusstseinszustand zu erreichen, wo subtilere Frequenzen mitschwingen. Erschöpfung ist entweder ein Wunsch oder ein Problem, aber sie kann auch eine Strategie sein, eine Strategie, um Kunst zu machen. Du sagst zu jemandem: Sieh dir das an, sieh es dir an, jetzt sieh es dir nochmal an, und wieder … nein, dieses Bild ist noch nicht fertig. Diese Intensität, diese Besessenheit, in der man die Zeit dehnt und die Menschen dadurch zwingt, hyperpräsent zu sein – darin sehe ich im Moment die Verantwortung der Kunst. Darauf zu insistieren, dass wir uns darüber Rechenschaft ablegen, wo wir sind.

HO: Wo siehst du die Grenze zwischen Tanz, der auf der Bühne zur Aufführung kommt, und rituellen Praktiken, wie die der Schamanen oder Shakers, die jenseits einer Bühne stattfinden?

MS: Beim Tanz auf der Bühne werden eine Reihe von Prinzipien oder Regeln mit einem Publikum geteilt. Bei schamanischen Praktiken und Ritualen geht es um bestimmte Ziele und das Wohl der Gemeinschaft. Schamanen werden von Geistern in andere Welten geführt, um Menschen aus der Gemeinschaft zu heilen. Das ist ein Dienst an der Gesellschaft. Wenn Menschen am Wochenende in Clubs feiern gehen, dann ist das eine Art improvisiertes Tanzritual, bei dem es um Begegnung, Loslassen und gemeinsam erlebte Momente der Ekstase geht. Dennoch herrscht sogar an Orten wie dem Berghain in Berlin ein relativ starrer Verhaltenskodex. Ich kann mir deshalb gut vorstellen, dass es in Zukunft immer mehr hybride, undefinierte, offene Orte geben wird, an denen man gemeinsam tanzen, loslassen, sich artikulieren kann und dadurch Strategien der Bewältigung und Heilung schafft. Ich hoffe, dass der Tanzkongress in Dresden so ein lebendiger, unkonventioneller Ort wird für kollektives Handeln und gemeinsame Ziele. Es wird eine fünftägige Zusammenkunft sein, die sich verworren und magisch zusammensetzt, die als eine Art soziale Choreografie funktioniert, innerhalb derer man sich trifft, austauscht, streitet und verändert. Ein dekonstruierter Rave und andere Formen des sozialen Beisammenseins und Tanzens sind da r essenziell. Der Rave müsste frühmorgens in der riesigen Halle in Hellerau beginnen. Er ist dann ein aufgeladener politischer Ort, wo die Konventionen des Nachtlebens keine Bedeutung haben. Ein Raum, in dem die Leute sich ganz unbefangen äußern können, weil es eine andere Art der Empfänglichkeit gibt. In dieser riesigen Höhle möchte ich etwas schaffen, das im Fluss ist, das die Gangart wechselt, so dass die Musik irgendwann langsamer wird, dann ganz abbricht, und ein anderer Raum zum Vorschein kommt, in dem man auf andere Weise präsent ist und sich zuhört.

HO: Der Tanzkongress ist auch eine Art utopisches Unterfangen. Es gab nicht viele Kongresse dieser Größenordnung – in der Weimarer Republik in den Jahren 1927, 1928 und 1930. Was wird es beim Tanzkongress für Rituale geben? MS: Ich interessiere mich gerade sehr für das Monte-Verità-Treffen in der Schweiz von 1917, bei dem Spiritisten, Anarchisten und Künstler auf diesem Berg zusammenkamen, um über alternative Lebensmodelle zu diskutieren. Beim ersten Tanzkongress 1927 wurde heftig über Dinge und Definitionen gestritten, die heute undenkbar sind, zum Beispiel was Tanz überhaupt ist, wie ein Tänzer zu sein hat oder welchen Nutzen der Tanz hat. Es ist auch immer wieder die Rede von der großen Party am Ende, bei der alle zusammenkamen. Da wäre ich gern dabei gewesen! Mich interessiert die gesellschaftliche Dimension von Tanz, Tanzgeschichte, heiligen Tänzen, kontemplativer Musik und Darstellungen, Kampfkunst. Mir ist wichtig, dass der Tanz nicht nur das Aufwärmen für den Diskurs-Teil ist, sondern dass beide in dasselbe Format integriert sind.

HO: Ich beschäftige mich gerade mit dem Phänomen der Tanzwut, auch Choreomanie oder Veitstanz genannt, das im 14. und 15. Jahrhundert in Europa auftrat. Ganz normale Leute in den Städten, nicht professionelle Tänzer, tanzten und tanzten, bis sie vor Erschöpfung umfielen. 1374 gab es so einen Ausbruch in Aachen. Wäre es nicht toll, wenn in Dresden die Tanzwut ausbräche?

MS: … oder eine Redewut! Wenn ich meinen Bewusstseinszustand ganz schnell ändere und meine Aufmerksamkeit auf etwas anderes außerhalb des gegenwärtigen Moments richte, habe ich das Gefühl, die Gesetze von Zeit und Raum außer Kraft zu setzen, mich durch andere Dimensionen zu bewegen. Ich glaube, es gibt eine Wahrheit, zu der man durch Körpertechniken gelangt. Tänzer wissen das, aber das sollte auch in anderen Bereichen verstanden werden: wie bestimmte Bewegungen unser Bewusstsein verändern. In Hellerau gibt es diesen großen Gartenbereich und ich hoffe, dass wir dort gemeinsame Rituale schaffen können, zum Beispiel um zusammen zu kochen und andere Formen des Austauschs zu erproben. Es wird sicher verschiedene Formen des Zusammenkommens und Feierns geben, aber auch des Zusammenkommens und Trauerns. Dresden wird keine fünftägige Party sein. Der Kongress wird eine Dramaturgie haben, in der Platz ist für die verschiedensten Dinge, für Meditation und Bewegung, aber auch für Gespräche über gewaltfreie Kommunikation zum Beispiel und Gerechtigkeit, oder über die Kraft der Gedanken.

Meg Stuart, 1965 in New Orleans (USA) geboren, ist Tänzerin und eine weltweit bekannte Choreografin. 2018 erhielt sie den Goldenen Löwen der Biennale in Venedig für ihr Lebenswerk sowie den Deutschen Tanzpreis für herausragende Interpretinnen. Damit wurde ihre herausragende Rolle für die Entwicklung des zeitgenössischen Tanzes gewürdigt. Die Kulturstiftung des Bundes konnte Meg Stuart gewinnen, die künstlerische Leitung für den alle drei Jahre stattfindenden Tanzkongress, der 2019 in Dresden ausgerichtet wird, zu übernehmen. Meg Stuart lebt und arbeitet in Berlin und Brüssel.

Hans Ulrich Obrist, 1968 in Weinfelden (Schweiz) geboren, ist ein weltweit renommierter Kurator für zeitgenössische Kunst. Seit 2016 ist er Artistic Director der Serpentine Gallery in London. Obrist betreibt seit mehr als 15 Jahren sein „Interview Project“, eine umfangreiche Kollektion von Interviews mit Künstler*innen, Musiker*innen, Architekt*innen und Filmschaffenden.

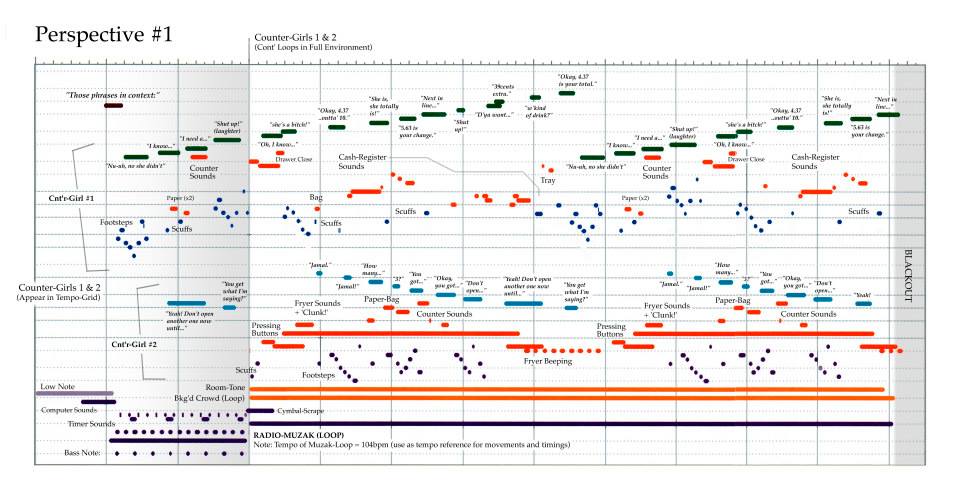

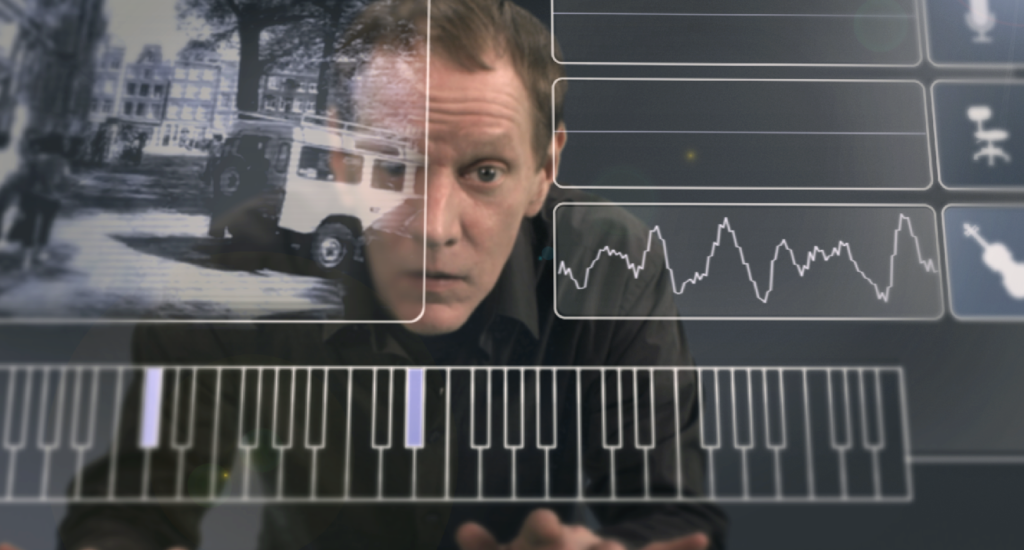

John Moran began his career in New York in the late 80s. Philip Glass is considered his mentor. In his operas J. Moran worked together with Uma Thurman, Iggy Pop and Allen Ginsberg. Since 2008 Moran has been producing mainly in Europe. In 2017 he worked on a new version of his opera “The Manson Family” in HELLERAU.

John Moran began his career in New York in the late 80s. Philip Glass is considered his mentor. In his operas J. Moran worked together with Uma Thurman, Iggy Pop and Allen Ginsberg. Since 2008 Moran has been producing mainly in Europe. In 2017 he worked on a new version of his opera “The Manson Family” in HELLERAU.