Beast Type Song

Sophia Al-Maria

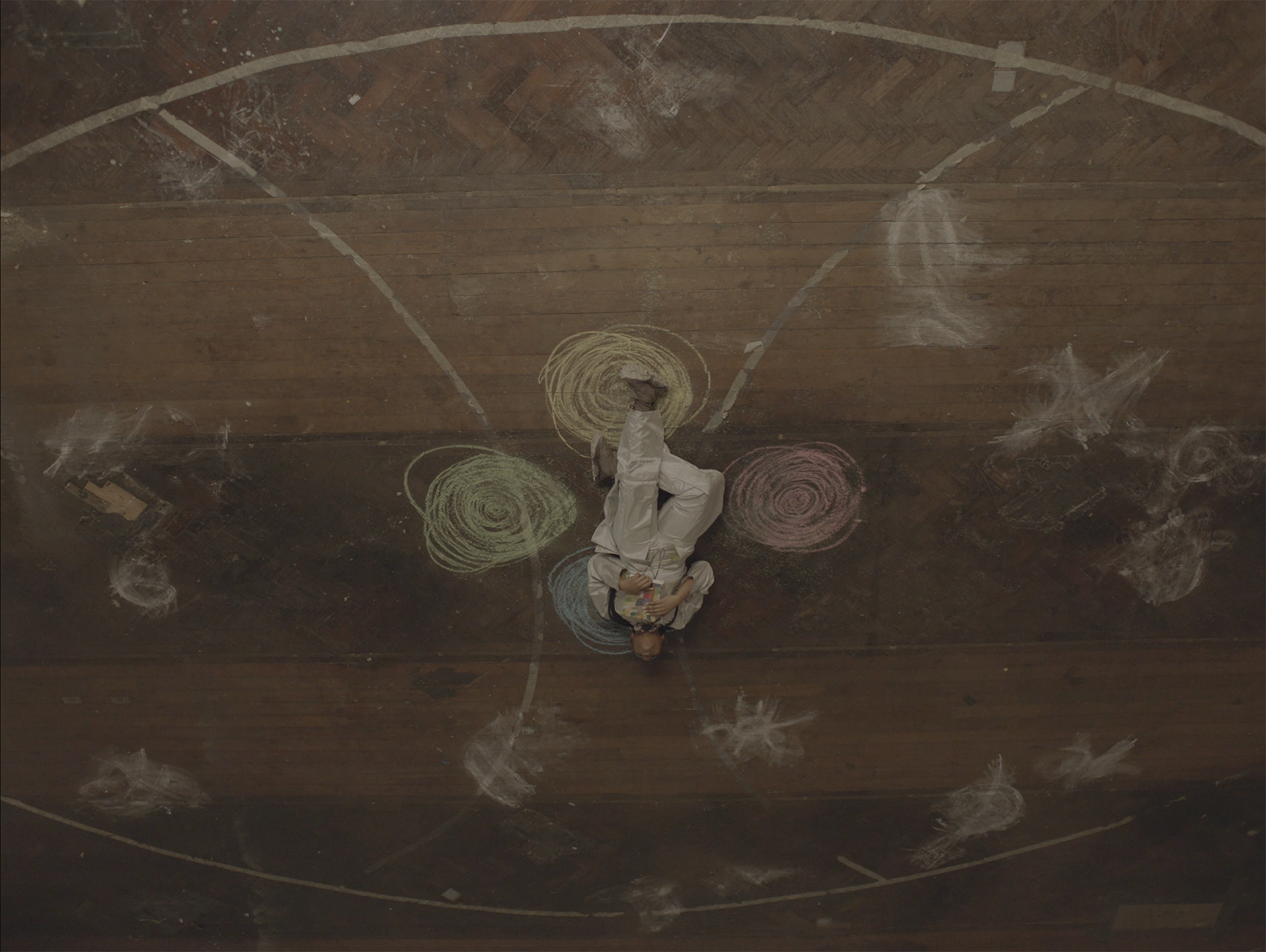

Beast Type Song (2019) is a single-channel video with sound in which the themes of language, education and writing are interwoven in an exploration of the erasure and revision of identities and histories from the past and future. The work, which is shown as a projection and lasts just over thirty-eight minutes, consists of a constellation of images and stories that come together to form an abstract and shifting landscape of conflict. The video consists of a collection of “revisions”, as Al-Maria calls them, and borrows its structure from the visual language of script editing. Just as each returned revision of a script is marked by different colours, each act of Beast Type Song is marked by an asterisk on a different coloured background: blue, pink, yellow, green, golden yellow, sand, salmon, cherry red, light brown. The video consists of nine such revisions. As an artist with experience as a scriptwriter, Al-Maria consciously uses her medium to illuminate obscured realities. Form and content intermingle through the use of revisions of type to address historical revisions. Beast Type Song was shot on the derelict former campus of Central Saint Martins School of Art and Design in Holborn, London, a site of important heritage for the education of many prominent British artists.

Beast Type Song was first exhibited as part of the Art Now programme at Tate Britain between September 2019 and February 2020. On 18/19 November 2022, it will be presented as part of the HYBRID Biennale 2022 in the Spero Saal at Festspielhaus Hellerau in collaboration with PYLON.

The screening is part of the PYLON-Lab programme COLLATERAL EXTINCTION, supported by the Kulturstiftung des Freistaates Sachsen. This measure is co-financed by tax funds on the basis of the budget passed by the Saxon State Parliament.

Sophia Al-Maria is an artist, writer and filmmaker. She grew up in the United States and Qatar before moving to Egypt to study comparative literature at the American University in Cairo. She then went on to study acoustic and visual cultures at Goldsmiths University in London.

The seemingly disparate sources of inspiration for Al-Maria’s multidisciplinary practice include pop culture, anime, Arabic poetry, science fiction and her personal experiences with pollution and climate change. The artist works primarily with film and narrative text, weaving compelling stories to process her thoughts and feelings about the future, especially in light of the current climate of extinction. Her recent work is increasingly concerned with the isolation of the individual through technology and consumerism as a substitute religion. Above all, with the question of the role of action and chance in being blinded by an uncertain future.

In Beast Type Song (2019) there are two pieces of music whose performers are unknown. One is the Quranic verse about the blood clot (العَلَق), performed by a young-sounding androgynous voice, and the other is the Arabic folk song The Dove Bird (طيرالحمام) – in the video, the dove it sings about is a recurring element. The song is first sung “live” in front of a Palestinian poster that hung in her living room during Al-Maria’s childhood. Towards the end, it is heard another time in the form of a YouTube clip. Uploaded in 2010 by the user Os66s, it shows a young woman leaning against a cushion on the floor. Hauntingly, yet quietly, she sings the song in the incoming light of a sunbeam. As I write this, the video already has over 1.6 million views, and every second comment laments the fact that the singer’s identity remains unknown to this day – after more than ten years. I’ve often wondered if the person in the video ever thought to come out as the performer of this song that was being bandied about, but perhaps anonymity was the necessary condition for her performance. The use of the clip that brackets Al-Maria’s video is fitting in that it is about the treacherous nature of language – the difficult terrain one enters the moment one utters anything.

At the beginning of the video, Al-Maria says she is working with a Shakespearean five-act structure. In the end, however, this does not correspond to the form in which this monster of a work sees the light of day: It is divided into some 13 chapters, with each section announced by an asterisk or other runic character against a changing background colour. In a collage that combines archival footage with live performance, Al-Maria assembles a frenetic chorus of dissident voices: some long silenced and mythicised, such as Michelle Cliff, Mohamed Choukri, Ghassan Kanafani, Shakespeare’s Caliban and others; but interspersed with them are contemporary protagonists such as the performance artist boychild, actresses Elizabeth Peace and Yumna Marwan, Al-Maria herself and a flock of white doves. They are the characters who drive the film forward, hesitant to be sure, bumpy and stuttering, occasionally intermingled with references to the “war with the sun” as described by Lebanese artist Etel Adnan in her book-length poem The Arab Apocalypse in 1989. At one point, Al-Maria shares her insider knowledge of the film industry, not only about the use of colour in script editing, but also about outrageous details such as the corrections made by a white man to the roles of non-white actors and actresses, probably involving the artist’s script for her 2020 TV mini-series Little Birds. We also learn that she turned down a commission to rewrite a future novel about the climate because she doesn’t want to be too pessimistic about the future because of her superstitions. In another chapter, introduced by a blood-red asterisk, “Yumna” – here a freedom fighter who has landed on a spaceship – asks “Sophia” if she is still busy writing, which she denies. The narrative part is like a matryoshka set: across all the diverse worlds the video opens up to us, Al-Maria and her friends remain sceptical about spoken words and their power to change anything. Nevertheless, they persistently but vigilantly keep trying.

In another scene, Al-Maria reads from Cliff’s 1991 essay “Caliban’s Daughter” as a torrential downpour pours over tall trees in the distance. The idiosyncratic synthesis that forms the Jamaican-American writer’s language, expressing her own thrown-together self – “sometimes civilized, sometimes ruinate” – a rejection of her own speechlessness, is associated with Edward Said’s concept of “third nature”. The term “ruinate” is distinctly Jamaican; it refers to formerly colonised and cultivated but now overgrown fields and plantations that have reverted to wilderness. Said’s “third nature” refers to the very condition that can be described as a restored being in the world that has overcome the ecological destruction created in decades of (neo-)colonial developments and is thus less tragic than our own status quo. Ultimately, the film’s protagonists are unable to find their way to unspoilt meadows, fields of thyme or forests of soap trees. Nevertheless, it is certain that they will not cease to be fearless roaring “beasts” in their third and 13th nature, improved and spurned and spat out again.

Bassem Saad